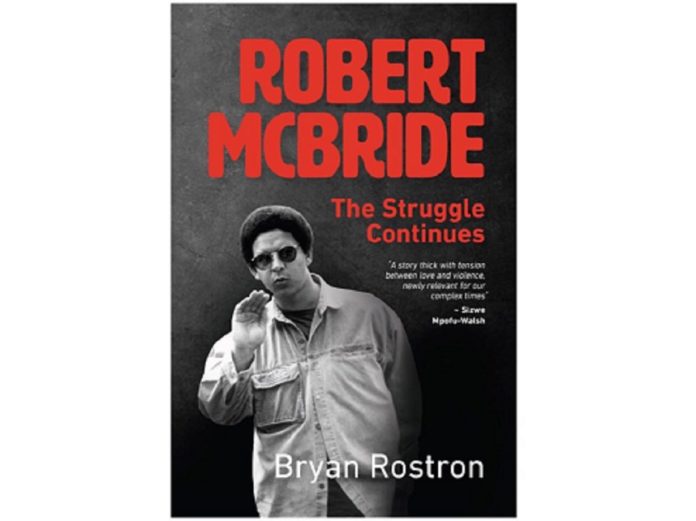

Robert McBride: The Struggle Continues is the story of Robert McBride and his comrades: the substation sabotage spree, rescuing a compatriot from the hospital and smuggling him to Botswana, the devastating Why Not and Magoo’s car bomb. Written by Bryan Rostron, the book has been updated to include McBride’s controversial life after the end of apartheid. In this extract, Mcbride describes being on Death Row.

Death Row is on a gentle rise overlooking Pretoria Central Prison. It is quiet up there in the high-walled citadel, and the other prisoners call it Beverly Hills. It has a fine view, but those who go in through the immense black iron gates are never intended to see the outside world again. There are no windows in ‘Beverly Hills’. ‘At first I could never sleep,’ said Robert McBride, prisoner 3737. ‘The white guards used to come and stare at me – the terrorist. I shouted, “Hey, whiteboys, what are you staring at?” Then I accepted I was going to die and thought, to hell with these people.

‘The first friend I had on Death Row was executed almost immediately after I got there. Edward Heynes was in for a prison murder and he was the first guy to speak to me. After I’d been there only two weeks he was given his notice of execution. Heynes had a rosary. He held it up like a rope and said, “I’m going to hang.” He was cynical and accepted it. I couldn’t accept it, but then the reality hit me. I’m going to die.

‘For Heynes, outwardly it was a joke. He laughed. It helped him get through it. There seemed to be no fear. The first day he was in the Pot, after he got his notice, he called to me in Afrikaans, “McBride – I told you they were going to get me.”

‘The night before an execution the other prisoners used to sing. In the first year there were no stays of execution and people were more passive and fatalistic, but then they began fighting back with appeals and stays of execution. In my first year, people were relying heavily on religion. They sang a lot, mostly hymns, in Zulu – “Rock of Ages” – and southern folk or soul songs. They’d sing “Climbing Up The Mountain”: “If I don’t see you.”

I’ll meet you on Judgement Day.” If it was a comrade being hanged, then they sang freedom songs. Freedom songs help build up your spirit. It would be songs about Oliver Tambo, or “What have we done?”, Senzeni na in Xhosa.

‘The night before an execution people are very sad. Then about eight o’clock in the evening the whole place stamps its feet. It makes your hair stand on end. Other prisoners sing the whole night. ‘The night Edward Heynes was to go I finally fell asleep on the table, my head in my hands, and I woke early. Everyone had been singing before.

Now it was very quiet…” In South Africa, the hangman was a busy man. During the previous decade there had been over 1 500 executions in Pretoria Central. Sometimes the queue for the gallows was so long that several were dispatched at the same time. For this purpose there were seven gallows all in a row. The gallows loomed large in the thoughts of those in Beverly Hills, and the men who were awaiting its immediate attention were kept in an isolation cell known as the ‘Pot’.

Condemned men were handed their notice of execution a week before the appointed dawn. In the Pot, during this week of preparation for the noose, the prisoner was permitted to scream and shout and sing as much as he liked. Families were issued with railway tickets to Pretoria for one last visit.

The ritual for preparing a man for his death was precise and unvarying. The condemned man had his height and weight measured to determine the exact drop necessary, while his neck size was checked to tailor the noose exactly. For his last supper, the condemned man was served a whole chicken – though the bird had been carefully deboned to prevent the possibility of a last-minute suicide attempt which might rob the hangman of his dues.

Executions took place at dawn. A chaplain would visit the subject before he was led through the final, fatal double doors. In front of him would be seven gallows, one of which had been specially rigged to his own personal specifications. The condemned man had his wrists tied behind his back.

And a hood placed over his head. The hangman stepped forward and fitted the noose, then pulled the lever. A trapdoor opened: the man was dispatched. There were so many executions that some of the relatives simply could not believe it. Death Row generated its own myths. One was that the condemned, the dawn they were led away never to be seen again, were actually transported to a bunker below a nearby hill, where they worked on dangerous chemical and radioactive weaponry. Others said that deep underground there was a mint where the government consigned them to work as slaves manufacturing money.

In fact, the body was carried out through the black iron gates in a plain black van escorted by a police car, to a cemetery where it was buried in the presence of state officials. Only later were relatives informed of the location and number of the grave. The cemetery to which the authorities allocated each corpse was ordained by colour of skin.

In May, when Derrick’s trial had finished, Doris travelled up from Wentworth to visit her son. He had lost a lot of weight. ‘It was terrible, that big black door,’ said Doris. Every time it groaned and rolled open it gave me the creeps. But when it was closing, clanging shut, it was worse. It had a terrible effect on me, that door.’

Slowly, agonisingly, Robert McBride began to reject the idea that he was going to die. He did not want to die. ‘At first when I was on Death Row everyone used to sing hymns,’ said Robert. ‘They were relying on religion.

They had no other hope.’ One of those who had turned to religion was Menzi Thafeni, a 20-year-old youth, already on Death Row for over a year for the killing of a policeman – for which he claimed he was innocent. ‘Every time they executed someone we felt it like our own day approaching,’ said Menzi. ‘When people were going to be hanged, I saw them pass by my cell. Sometimes they would say, in Xhosa, “We are on our way to heaven.” And as they passed they greeted me, saying, “It is over.” There were 32 steps to where they hung. After a year they took my friend Konze.’

Jacobus Konze and Menzi were such close friends they were known as twins; then Konze was given his notice and taken to the Pot. From the Pot, Menzi could hear his friend shouting that if God in the Bible could save Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego from the fire, why could He not save him? At the last minute Konze was granted a stay of execution, and returned to his cell pending a clemency appeal.

‘When a person comes back from the Pot, they can never be the same person again,’ said Menzi. ‘It is like they have come back from Hell. They have been to visit the death.’ Konze, Menzi felt, was already dead in his heart. His appeal was turned down, and Jacobus Konze returned to the Pot for the second time: ‘On 7 March they came to him and told him to pack his things. On 14 March he was taken to the gallows machine. When he was taken away that morning he was shouting for me as he was walking. He shouted, “Menzi, my time is over now, but you must not be in sorrow, you must not cry.”

‘Then when I heard the bang of that machine, that is the time I know it is finished. Afterwards one of the warders came to me and said, “Yes, Thafeni, your twin is gone now.” This man was laughing at me.’ One of the torments of Death Row was that the lights were never extinguished.

There was no retreat, no respite; the bulb burned in the solitary cells, bare and bright, forever. ‘Robert greeted me and shared things with me and we became friends,’ said Menzi. ‘He became like an older brother to me. He taught me English because my English was not very good. We shared our fears and he gave me strength. He taught me that I must be realistic, but strong as a man, and that I must never give up hope. It was good for me because I became strong. We talked about our future – how to behave ourselves if we ever got out. We also talked about death, that we must be strong and show them that we are not afraid of death. There is no suffering in that moment: the waiting is worse.’

Robert found that the only way to cope with the prospect of being handed his own notice of execution at any moment was to try and numb his feelings – not to think too much, never to get excited, above all to avoid emotion. Gradually, however, there were glints of hope.

‘There were some stays of execution, and suddenly there was less dependence on religion,’ said Robert. ‘Now there was real hope – not just pie in the sky. There was hope of reprieve and there were even last-minute stays of execution, at six a.m., moments before . . .

‘People would be laughing, excited, everyone would be celebrating. You are alive, you are coping. ‘I began fighting, I became obsessed by it. I began to think about it all the time. My motto became: What have I done today to save my life?